Back to Feed

Victorian · Battle Creek, Michigan

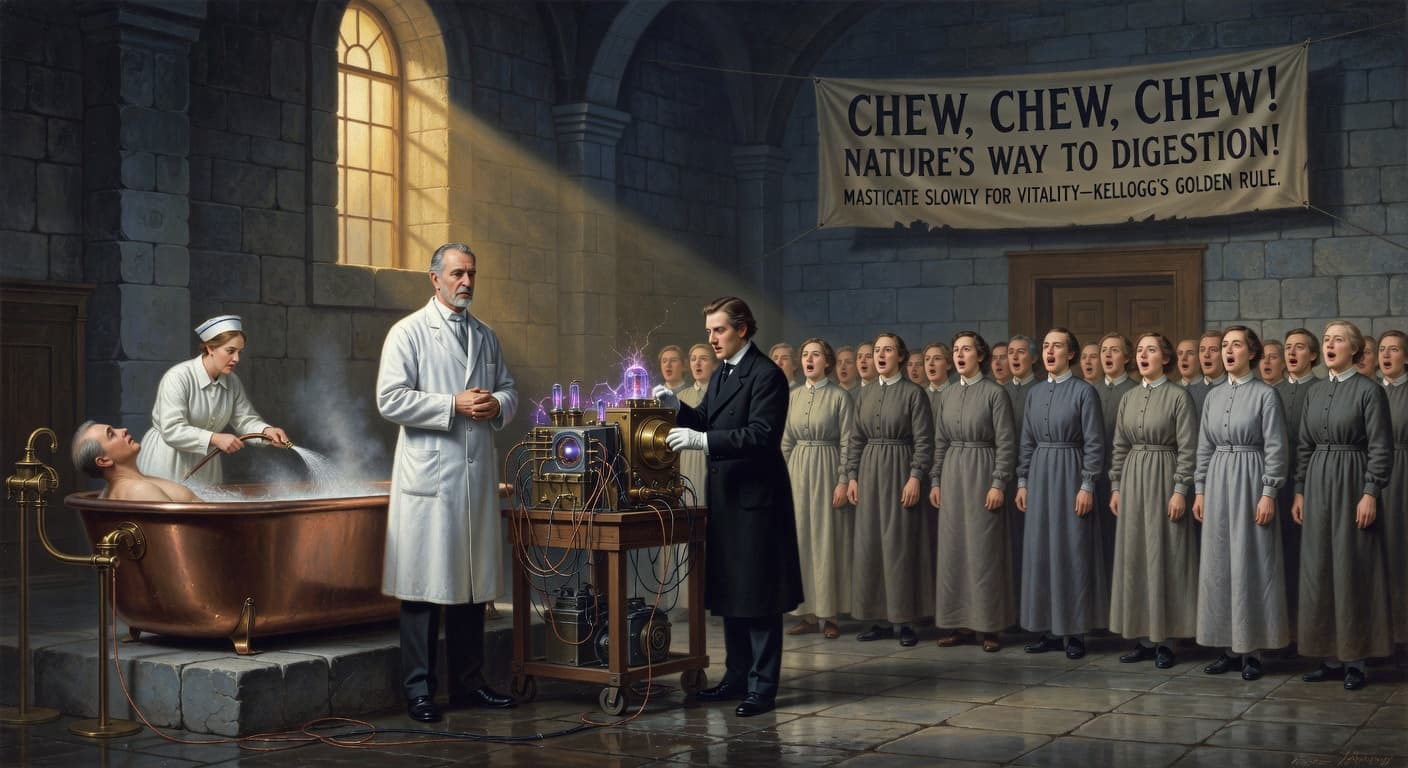

Dr. Kellogg's Sanitarium: Enemas, Electrical Eyeball Treatments, and the Chewing Song

★ 8.2 / 10medicinequackerysanitariumhealth

In 1876, John Harvey Kellogg — physician, Seventh-day Adventist, and fervent believer in the curative power of the colon — took control of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan and spent the next 67 years making it the most famous health resort in America. At its peak the institution spread across 30 acres and more than 30 buildings, accommodating over 1,300 guests at a time. Its patient list included Henry Ford, Amelia Earhart, Warren Harding, John D. Rockefeller, and Sojourner Truth. The treatments it offered were sometimes brilliant, frequently eccentric, and occasionally difficult to distinguish from theater. Kellogg was a genuine progressive on matters of nutrition: he invented corn flakes, peanut butter, soy milk, and a range of meat substitutes decades before vegetarianism entered mainstream medicine. But his conviction that the intestine was the seat of all disease led him to supplement these innovations with industrial-scale colonic irrigation. Guests received multiple enemas daily — a practice Kellogg extended to almost every patient regardless of complaint. He was an equally passionate disciple of Horace Fletcher, the "Great Masticator," who prescribed chewing each bite of food at least 40 times before swallowing. Kellogg led diners in what his biographers call the "Chewing Song." He was not doing this ironically. From telephone parts Kellogg assembled an electrical device that administered what he called "sinusoidal current" directly to patients' skin. He claimed it could treat lead poisoning, tuberculosis, and obesity. When applied directly to the eyeballs — a procedure he offered and patients accepted — he maintained it corrected vision disorders. He was also a lifelong opponent of masturbation, which he blamed for poor posture, cancers, and dozens of other conditions, and designed several devices intended to prevent it in children, which he described in clinical publications. The sanitarium declined in the Great Depression, was bought by the U.S. Army in World War II, and became a federal building. It stands today as the Hart-Dole-Inouye Federal Center in Battle Creek. Kellogg's cereal innovations survived him; his electrical eyeball treatments did not.

Score Dimensions

Original Source

wikipedia.orgLike

Dislike

Skip

Save